Saudi Women: Perfect Candidates? | (dot)gender

(dot)gender | A space by LORENA STELLA MARTINI

The Saudi Arabian film director and screenwriter Haifaa al-Mansour can definitely be called a pioneer: in 2012, her movie Wadjda was the first ever to be entirely shot in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, and the first ever to be directed by a Saudi woman. Back in 2012, al Mansour’s story was about a 10-year-old Saudi girl longing to ride a bicycle – something she was prevented from doing because of her gender. The movie, which al-Mansour had to shoot while hiding in a van, was a sort of breakthrough which shed light on women’s rights in the Kingdom; a year later, the ban on women cycling was partially lifted.

7 years after the release of Wadjda, al-Mansour chose again her native Saudi Arabia as the setting of her movie The perfect candidate (2019), which was selected as Saudi Oscar contender for the year 2019. This time, al-Mansour didn’t have to hide anymore to direct the shooting of the story of Maryam, a young Saudi medical doctor who works in a small town’s clinic, proudly drives her car and runs for the municipal council elections.

The movie provides an interesting cross-section of the evolving – and surely paradoxical – situation women are currently living in Saudi Arabia: Maryam is allowed to travel alone to Dubai for a medical conference, yet she is stopped at the airport because her travel permit has expired, and it is exclusively up to her father – her

mahram (guardian) – to renew it. The young woman has a job as a doctor in the local clinic, but her daily work routine is made difficult by the sexist attitude of her fellow colleagues and of her patients, who prefer being treated by male nurses than by female doctors.

Maryam is eligible to vote and run for the municipal elections – a right Saudi women have finally gained in 2015 – but she is not supposed to directly address male voters, and she shoots her campaign video with even her eyes fully covered. Helped by her proactive sister, she manages to throw an all-women successful fund-raising event for her electoral campaign, yet when she asks participants if they will vote for her, they mainly answer that they are not going to cast their ballot, or that they cannot disobey their husbands’ indications about whom to vote.

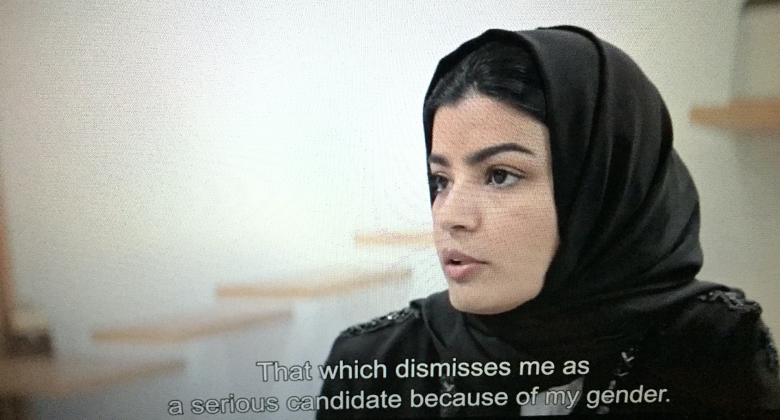

Maryam’s candidacy is not initially animated by a strong social conscience – her race is kind of random, and her main objective is paving the bumpy road leading to the clinic where she works. Yet men’s paternalistic attitude towards her endeavour makes her more and more determined to fight against the prejudice that dismisses her as a serious candidate because of her gender. As she explains during her first (and only) TV interview, her candidacy does not only concern women and so-called “women’s problems”, but it is something which could benefit the whole community.

All in all, The perfect candidate is a bittersweet invitation to reflect upon social change, its acceptance and its contradictions in a country where women are increasingly “allowed” from the top to engage in previously prohibited activities, while at the same time conservative, patriarchal social norms remain in place, and gender segregation makes women’s lives extremely complicated. While in the last few years Riyadh has often been praised for its progress in the domain of women’s rights, in 2018 thirteen women’s rights defenders were arrested in the country with accusations linked to their activism. The cases of two of the five women who are currently still in detention have been recently referred to the Special Criminal Court, specialised in terrorism and threats to national security.