Unorthodox – The Scandalous Rejection of my Hasidic Roots | (dot)gender

(dot)gender | A space by LORENA STELLA MARTINI

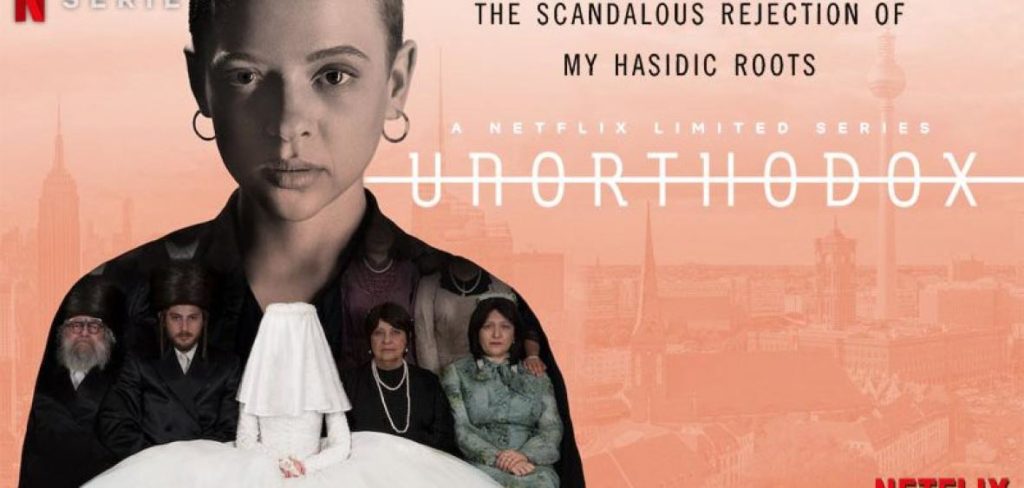

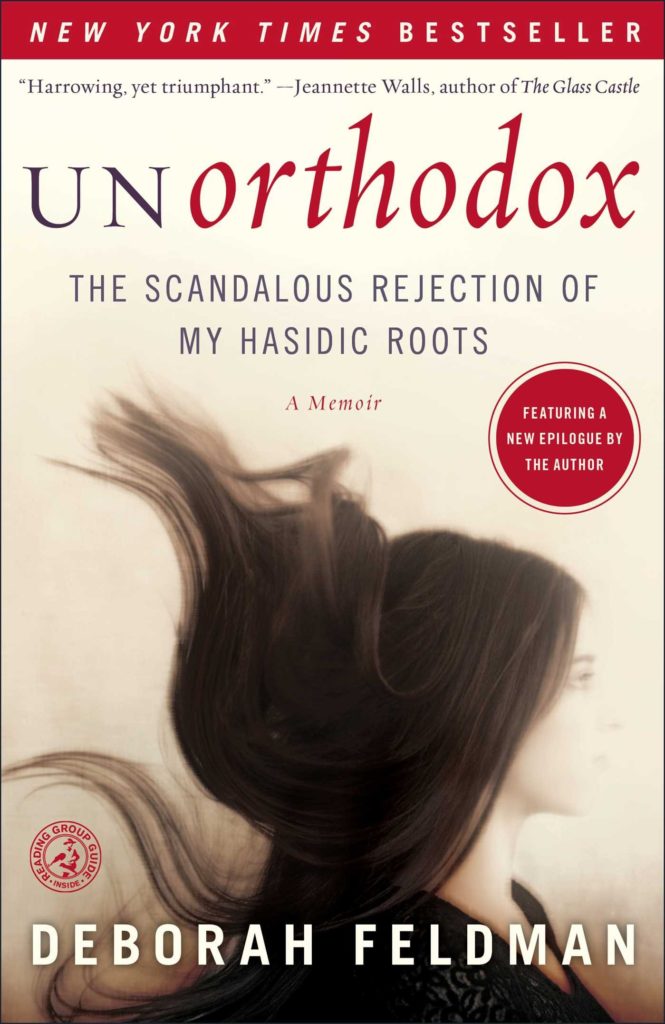

While in quarantine, I had the chance to watch the short series titled “Unorthodox” (2020), based on the story of Esty, a young Jewish girl escaping from an ultra-orthodox Satmar Hasidic community based in Williamsburg, New York. Since I knew almost nothing about Hasidic Judaism, I decided I wanted to discover more and started reading “Unorthodox – The Scandalous Rejection of my Hasidic Roots” (2012) by Deborah Feldman, namely the memoir that inspired the series recently produced by Netflix.

The author, now a writer based in Berlin, recalls her childhood and adolescence in the Satmar Hasidic community of Williamsburg – one of the largest in the world – spent with her old, pious grandparents and her extended family, after her mother has left the community as well as Devoireh‘s (this is Feldman’s Jewish name) retarded father. The society emerging from the author’s words is an extremely traumatized one, built on the ashes of the Holocaust and on the sense of guilt deriving from the genocide: indeed, Hasidic Jews believe the Holocaust to be a punishment sent by God on Jews to make them repent for their attempts to integrate into Western culture.

In this rigid framework, everything is ruled according to very strict rules, including gender roles, which follow accurate, carved-in-stone traditions. Thus, the author meticulously portrays her condition first as a girl and then as a young woman in the community: the almost complete absence of contacts with the male counterpart until the arranged marriage, the absolute obligation to be modest in her appearance and behaviors, the total lack of a secular education and the extremely short duration of her religious schooling. Indeed, within the community, she has no hope to pursue her studies, no matter how gifted she might be: as a girl, she is supposed to graduate from religious high school at the age of sixteen, to be married off to a fellow member of the sect and fulfill her “natural” role of bearing children and looking after the family.

While on one hand her wedding at the young age of seventeen represents Devoireh’s chance to escape from the oppressive control of her family of origin, on the other it creates a whole new series of obligations for the young bride, namely the social pressure to consummate the arranged marriage without even knowing what sex was before taking kallah (marriage) classes, the obsession with female purity, corroborated by a series of complicated rituals, or the new restrictions to her freedom imposed by her mother-in-law.

What is interesting to remark, as explained by Feldman herself in an interview, is that the extremely patriarchal traditions that female members must abide by within the community seem to be first and foremost perpetuated by women themselves, most of whom are portrayed as strongly determined to nurture the same radical values of extreme modesty, isolation from the outside world, gender separation and complementarity they have grown up with.

In Devoireh’s words, instead,

«they make it out so that genders are like different species, doomed to forever misunderstand each other. But really, the only differences that exist between men and women in our community are the ones that are imposed on us. Underneath it all, we are all the same». (p. 145)

Far from being an ethnography of a Satmar Hasidic community, this memoir is the personal story of the author and of the feelings of extreme discomfort and lack of sense of belonging that have accompanied her life until her final decision to break free and leave her Hasidic roots behind.

«On the outside, I keep kosher and dress modestly and pretend to care deeply about being a devout Hasidic woman. On the inside, I yearn to break free of every mold, to tear down ever barrier ever erected to stop me from seeing, from knowing, from experiencing». (p. 233)

A further suggestion: the documentary “One of us” (2017) on three Hasidic Jews willing to leave their ultra-orthodox community, available on Netflix.