A Story of Migration and Failed Integration: The Beta Israel Community as a Case Study | (dot)migration

(dot)migration | A space by EMILY TASINATO

Ethiopian Jews in 4 pills:

(1) Ethiopian Jews traditionally refer to themselves as Beta Israel (House of Israel), claiming to be descended either from Menelik I, the son of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, or from the Tribe of Dan, one of the ten lost tribes of Israel.

(2) Because of their faith, during the centuries they suffered for prejudices and discriminations at the hands of the Christian neighbours, and in the 19th and 20th century they had also been forced to convert to Christianity. In fact, the term Falashas, a derogatory designation in Amharic meaning “strangers” or “migrants” in referring to Jews of Ethiopian origin, was originally adopted by the Beta Israel community itself to dub every Ethiopian Jew converted to Christianity.

(3) During the 1978 “Red Terror” campaigns led by the Derg, the military junta that ruled Ethiopia from 1974 to 1987, a consistent number of Jews were tortured, imprisoned and massacred. Because of the civil war and the persecutions, by the early 1980s Ethiopian Jews began to move from Gondar and Tigray provinces in the north of Ethiopia to Sudan, settling in refugee camps with the hope to arrive in Israel[1]. Eventually, roughly half of the community arrived in the “Holy Land” via two large-scale operations: “Operation Moses” in 1984-1985 and “Operation Solomon” in 1991.

(4) According to the Central Bureau of Statistics in Israel, approximately 155,300 Ethiopian immigrants are living in Israel today, around 1,6% of the total population. Of these, 67,800 were born in Israel[2].

Ethiopian Jews represent one of the ethnic-minorities inside the multi-faced and complex Israeli society. Even though the question of their (failed) integration in Israel is very often neglected by the international press, it concerns an issue worthy to be analyzed and discussed because it put under the spotlight one of the main plights inside the State of Israel, notably cultural racism. Indeed, on the heels of the protests that have been shaking the country after the murder of Solomon Teka, a 19 year-old Ethiopian Israeli man shot and killed by an off-duty police officer in the town of Kiriyat Hayim near Haifa on 30 June 2019, Pnina Tamano-Shata, one of the two Ethiopian lawmakers in the Knesset, wrote in a Facebook post: “The fracture and the rage created are the result of years of exclusion, discrimination, racism and hard trampling”[3]. Hence, integration of Ethiopian Jews of first and second generation into Israeli society continues to represent an ongoing challenge.

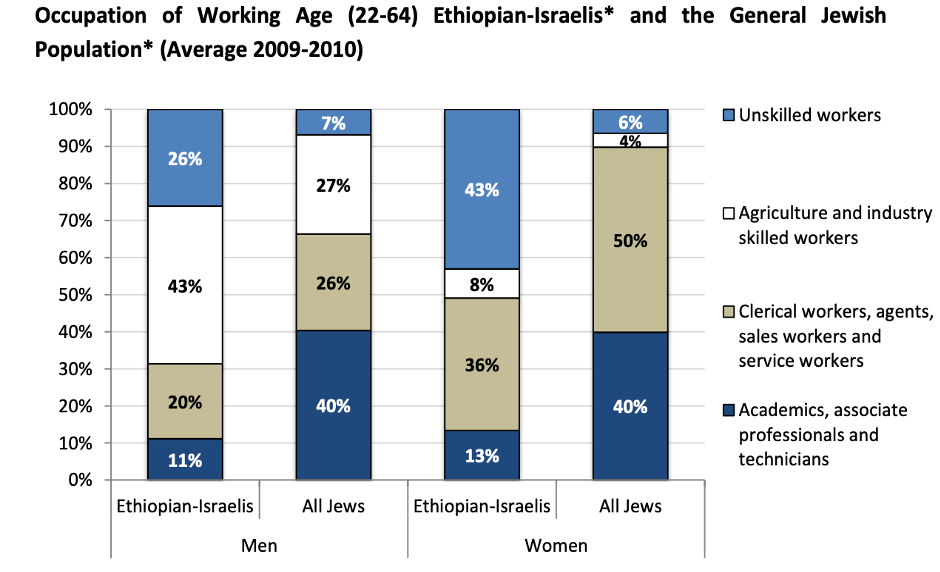

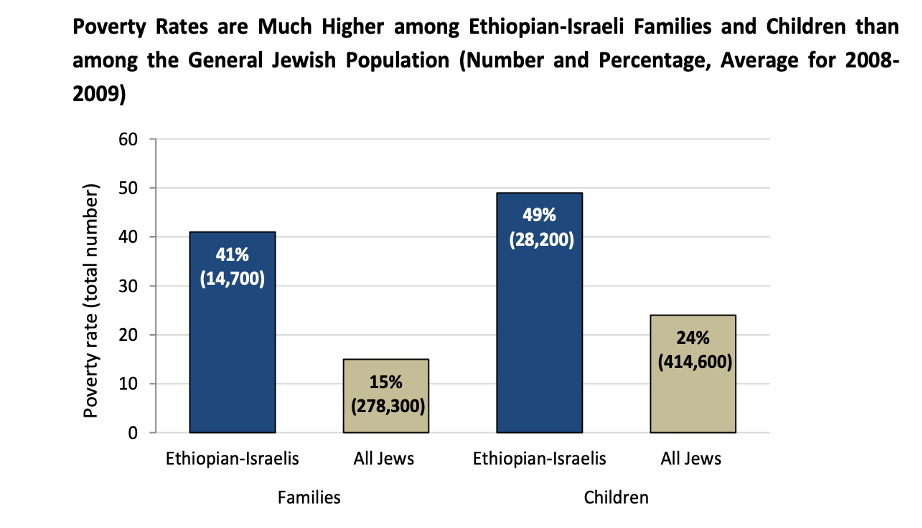

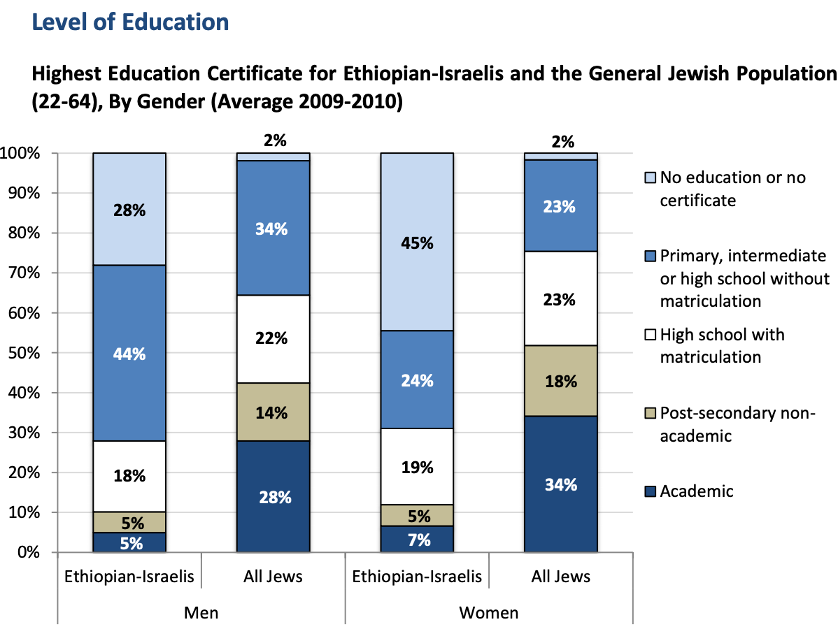

In this regard, in his research-work conducted with students and more broadly with youths of Ethiopian origin in the city of Haifa – Becoming a Black Jew: Cultural Racism and Anti-Racism in Contemporary Israel[4] –, Uri Ben-Eliezer, a political sociologist and Chair of the Department of Sociology at the University of Haifa, arguments how Ethiopian immigrants of both first and second generation are facing a “mechanism of exclusion, discrimination, and control” committed systematically by Israeli society and perpetrated by its governmental policies. More specifically, according to the author, it is since their arrival in Israel that Ethiopian Jews have been considered a matter of distress, gradually becoming within a few years victims of a “racism [that] encourages the preservation of these [cultural] differences, while it warns against any attempt to assimilate those who are different in their appearance, style of life, and perception of reality, and who may thus threaten the unity and integrity of the whole nation”. In this sense, Ethiopian (Israeli) Jews are targeted as “others”, and for them there is no place in Israeli society. Firstly, the resulting process of marginalization, due to the lack of social inclusion and social cohesion into Israeli community, is relegating Ethiopian Jews to the bottom of the socio-economic ladder. If compared to the members of other ethnic groups living inside Israeli society, Israelis of Ethiopian origin have lower levels of education, lower employment rates and are more likely to be employed in low-skilled occupations. Indeed, education is a strong driver of social mobility and according to the Central Bureau of Statistics, in 2019 the Ethiopian-Israeli student population enrolled in institutions of higher level represents only 1,3% of the total student population in Israel[5].

On this matter, a 2012 detailed report by Myers-JDC-Brookdale Institute highlighted this existent socio-economic gap between Ethiopian-Israelis (referring to Israelis born in Ethiopia and Israelis with one or more parents born in Ethiopia) and the general Jewish Population [6].

Moreover, this socio-economic marginalization has also acquired a physical dimension in relation to what Uri Ben-Eliezer defines “a politics of spatial separation” and a de facto segregation. In this regard, emblematic is the role played by the absorption centres to which Ethiopian immigrants were sent at their arrival in Israel during the two big waves of migration mentioned above, and where they remained for a long period of time, sometimes for many years. These centres, using Uri Ben-Eliezer words, have contributed to create “a culture of dependence in which the immigrant, now an Israeli citizen [in fact, in 1975 the Israeli government decided to apply the Law of Return to Ethiopian Jews too] lost most of his or her freedom”. Furthermore, today a de facto segregation is even more visible both in the educational system, where it is unlikely that students of Ethiopian origin go to school with their Israeli peers, and in the social housing allocation policies in poor neighbourhoods at the outskirts of the cities. Finally, also the problem of the Jewishness of the Ethiopian immigrants rose by the Ashkenazi ultra-orthodox group, the highest authority in crucial religious questions, is contributing to increase these discriminatory attitudes and a cultural racism towards the Beta Israel community. For instance, only last year the Chief Rabbinate Council formally recognized the Beta Israel community’s Jewishness.

This report Why Ethiopian Jews are Building a Movement Against Racism in Israel (March, 2020) by VICE News reflects on cultural racism towards Ethiopian Jews into Israeli society, and on activism among young Ethiopian Israelis that since 2015, after the police beating of Dama Pakada, an Ethiopian-born IDF soldier, have led the protest movement against racism and police brutality, calling the Knesset for a systemic reform.

[1] Minority Rights Group International, “Ethiopia, Beta Israel”, updated January 2018. https://minorityrights.org/minorities/beta-israel/

[2] Ethiopian National project, “Ethiopian-Israelis”, updated 2020. https://www.enp.org.il/en/pages/Ethiopian_Israelis/#:~:text=Approximately%20155%2C300%20Ethiopian%20immigrants%20are,the%20general%20population%20(3.03)

[3] Ilan Ben Zion, “Anger of Ethiopian Israelis boils over after killing of teen”, Financial Times, July 19, 2019. https://www.ft.com/content/dd171788-a17f-11e9-974c-ad1c6ab5efd1

[4] Uri Ben-Eliezer, “Becoming a black Jew: cultural racism and anti-racism in contemporary Israel”, Social Identities 10, n.2 (2004): 245-266.

[5] Ethiopian National project, “Ethiopian-Israelis”, updated 2020. https://www.enp.org.il/en/pages/Ethiopian_Israelis/#:~:text=Approximately%20155%2C300%20Ethiopian%20immigrants%20are,the%20general%20population%20(3.03).

[6] For further information: Myers-JDC-Brookdale Institute, “The Ethiopian-Israeli Community: Facts and Figures”, Report, February 2012. https://www.enp.org.il/pics/database/more_data/25_file.pdf