Deconstructing the Role of the Military in the Middle East. The Case of Turkey’s Tutelary Regime at the Turn of the Millennium

ANNALISA GUARISE

INSIGHT #24 • NOVEMBER 2022

INTRODUCTION

One of the most glaring features of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) is surely the persistence of authoritarian regimes. Despite moderate experimentation of political pluralism, the region continues to be solidly non-democratic and coercive control ultimately remains the favoured means to exercise political power. In a society that still lacks the political representation of different interests and consciousnesses, the military occupies the space left empty by actual parties.

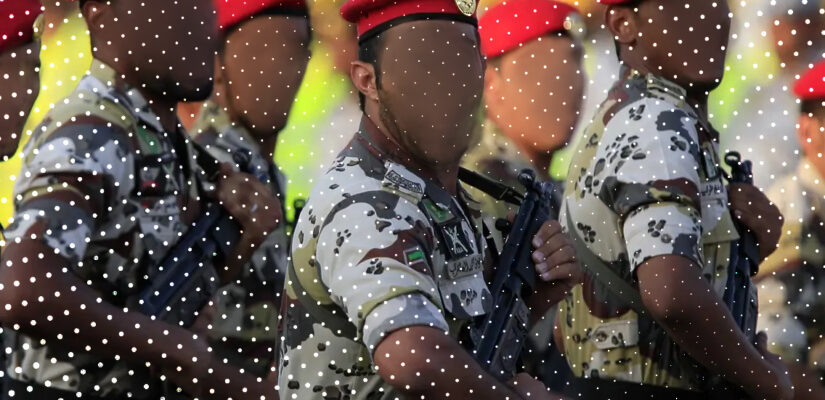

This paper aims to analyse the role of military forces within the Middle East arena, investigating the structural reasons that gave and still give strength to this social class. A concrete and relevant example is provided by the case of Turkey: having experienced four successful coups d’état in a time span of approximately forty years (1960-1997), the country happens to be an interesting laboratory for the analysis of the evolution of civil-military relations.

The first part of the paper will review the literature’s explanations for MENA countries’ resistance to democratization. Unfortunately, the traditional perspective lists the prerogatives of which the Middle East – ME is lacking rather than focusing on the exceptionalism of the region. Instead, in addressing the explanations for the relevance of the military, the analysis must focus on the current conditions that enable a robust authoritarian apparatus to last. Once this coercive apparatus is in place, the scenarios where the civil-military balance turns in favour of the military are multiple, ranging from a partial to a total autonomy of the military from the civil rule. In order to contain such interferences, over time authoritarian rulers have put in place “coup-proofing” strategies that, however, may result in a loss of the army’s efficiency.

The second part of the paper will narrow the focus to a specific case-study: Turkey. The Turkish Armed Forces – TAF have gained widely recognized relevance due to their historical contribution in the state-building process. Since the Ataturk rule, the military has projected itself in the role of guardian of the Republic and of its Kemalist principles. Consequently, the army’s involvement in politics has been justified by this responsibility to protect the state from both domestic and foreign threats: since its shift toward pluralism in the 1950s, the country has experienced constant interferences of the Armed Forces in its political life, especially through the practice of the coups d’état (in 1960, 1971, 1980 and 1997). This privileged role of the military persisted under tutelage until the new millennium: external changes such as the prospect of EU membership, the Iraq War and the situation in Cyprus, combined with the stabilization of the internal situation due to the AKP government’s administration, have determined a shift in the narrative. The consequent reshaping of both the public understanding of the military and the military’s self-perception within the political realm can in fact explain the failure of the 2016 coup.

*PART 1*

Resistance To Democratization

The resistance of Middle Eastern (ME) countries to democratization is an issue that has been broadly addressed in the literature. Traditional explanations approach the problem trying to identify the prerequisites for democratization that the Middle East seems to lack. From these analyses, five main elements result to be particularly meaningful.

The first detected element is the weakness of civil societies (Norton 1996; Wiktorowicz 2000, 43–61). Many scholars agree that this condition prevents from constituting a credible counterweight able to challenge authoritarian regimes and the military apparatus. A weak civil society stops citizens from being actively involved in basic democratic exercises, such as the practice of labour unions and collective deliberations, determining a lack of foundation for a potential regime change. Secondly, in many ME countries the economy remains strictly state-controlled, precluding the consolidation of an independent sector that could act as counter-power to the authoritarian state. The third factor is related to the overall social conditions of the population: citizens are generally poor, with low rates of literacy and separated by significant inequality. Consequently, neither the masses nor the elites choose to engage with democratic practices: the former because they cannot afford it, and the latter because they have no interest in changing their privileged status quo. The fourth element links the lack of democracy in the ME with the geographical collocation of the region, i.e. at the periphery of Europe, the real epicentre of democratization. Lastly the cultural element, which is significantly relevant when it comes to the religious dimension: according to some, Islam is in fact considered especially incompatible with democracy (Kedourie 1994).

These analyses show that the Middle East and North Africa countries lack the very prerequisites for democratization. Eva Bellin, in a largely cited paper, supports the idea that none of these explanations are actually fully satisfying, because they fail to consider the exceptionalism of the region (Bellin 2004, 139-57). According to Bellin, the question to tackle when addressing democratization in the MENA is not why democracy there has failed to consolidate, but rather why the majority of MENA countries have not started a transition toward it at all. In 1979 Theda Skocpol studied the elements that determine the outcomes of a revolution, finding that great relevance is covered by the state’s capacity to maintain the monopoly over the means of coercion (Skocpol 1979, 32). This means that the very coercive apparatus of the state determines the success, the failure or even the non-occurrence of a regime revolution. Building on these findings, Bellin theorizes that the MENA exceptionalism doesn’t lie in the absence of certain prerequisites for democratic transition, but in the current conditions that enable and strengthen a robust authoritarian apparatus in those countries. This shift in perspective is fundamental, because it allows us to deepen the present coercive structure of ME countries instead of focusing on what they are lacking.

Bellin thus introduces the concept of robustness of a regime’s coercive apparatus. More in detail, she explores the conditions that can determine the loosening of this coercive capacity, potentially enabling society to experiment with democratization. First, the maintenance of the military’s fiscal health: when salaries and ammunition supplies are no longer granted for the military corps, the superstructure disintegrates from within. When it comes to MENA countries, this issue does not arise since most of them allocate a robust share of their revenue to their security apparatuses (SIPRI 2021). Second, the maintenance of international support networks: especially for countries that have been recipients of massive foreign support, a withdrawal of such aids might trigger severe financial consequences for the regime. As for the ME, many countries have enjoyed financial support during the Cold War in return for their loyalty to one of the two great contenders. However, the – mostly American – security concerns related to the instability and strategic importance of the region have determined a continuation of international patronage after 1989 as well. The third element Bellin focuses on is the level of institutionalization of the military apparatus, that has to be intended in the Weberian sense, i.e. a rule-governed, predictable and meritocratic structure, where there are the conditions for developing a military identity separate from the state. This is, more specifically, an inverse relation: the less institutionalized the apparatus is, the less open it will be to reform. In many MENA countries, the coercive apparatus is driven by patrimonial logic, thus where the military is linked to the political regime through bonds of blood, sect or ethnicity, and career advancement is determined by political loyalty rather than merit. As a consequence, transitioning to democracy in post-patrimonial regimes is particularly challenging. The fourth and last predictor is the level of popular mobilization. The violent repression of a small number of citizens may not be so problematic; but when the civilians are a multitude, the use of lethal force may in fact be very costly in terms of institutional integrity, domestic legitimacy and international support. These last two points partially help to understand the different national responses to the 2010s popular uprisings: in Tunisia and Egypt the military recognized that their institutional interests didn’t depend on the survival of the political regime. Consequently, in these countries the military didn’t shoot the protestors, while the contrary has happened, for example, in Bahrain.

The civil-military problematique

These last points trigger a further reflection about civil-military relations, a broad field of study that tries to tackle one fundamental question: “quis custodiet ipsos custodes?” (Juvenal II century, lines 347-48), who will guard the guardians? Following up on this point, we could cite Peter Feaver’s concept of “civil-military problematique”, i.e. the challenge of keeping a military effective army, able to do anything the civilians ask it to, but still subordinate enough to remain within the civilian rule mandate (Feaver 1996, 149-50).

Steven Cook displays an interesting analysis about the interplay of military and civil forces, narrowing the focus on Egypt, Algeria and, before the more recent developments, Turkey’s multi-layered institutional orders (Cook 2007). He argues that these regimes are characterized by an indirect military rule: the military didn’t establish an open-air military dictatorship, but instead they handed direct control over the government ministries to its civilian allies, thus securing its privileged position while establishing shell pseudo-democratic institutions. This institutional façade allowed military officers to remain in control of the political developments through informal ties and control mechanisms, while letting other civilian actors to bear the burden of governing and of the public discontent.[1] Moreover, Cook underlines that exactly because these civilian institutions are subject to an indirect control of the military, they are also completely reversible: the military may tolerate civilian discontent only up to the point when there is a serious threat to the regime and thus to the military privileged position. In that case, the military would be ready to unhinge the institutional façade and re-establish its order.

Expanding on this line, in 2000 Mehran Kamrava examined different ways to deal with the above-mentioned dilemma in terms of the resulting regime structure: first, military democracies – such as Turkey and Israel – that present democratic institutions but also military corps that enjoy a certain degree of autonomy from the civilian rule while exercising a significant political influence; second, regimes such as Egypt, Iraq or Algeria, ruled by autocratic officer politicians that are dominated by military commanders; third, oil monarchies, that present small military forces partly constituted by foreign mercenaries, and the civic myth monarchies such as Jordan and Morocco, where a large army enjoys a certain degree of autonomy, while higher officers are benefited with privileges in exchange for their loyalty to the regime (Kamrava 2000, 70-91).

In order to maintain political control, leaders have to strip the military of the means and motive to challenge the regime. To protect themselves from such threats, authoritarian rulers have over time developed a variety of “coup-proofing” strategies, even if they continue to rely on their officers’ loyalty and coercive capacity to stay in office (Quinlivan 1999, 133). Risa Brooks recalls several ingredients for political control over the military (Brooks 2004, 132-40). One of the firsts barriers against military interventions is identifying and maintaining a social base, outside of the military establishment, that supports the regime. In fact, from the political leader’s point of view, popular dissatisfaction and thus opposition may lead, on the one hand, to an increase in the importance and public profile of the military, reinforcing the leader’s dependence on it, and on the other to testing the not obvious loyalty of the military junior officers when asked to repress the civilians. A second political control technique is to create alliances with minority groups, especially if they are implicated in the repressive activities of the regime or are objects of resentment for their privileged status: in that way, they would have strong personal interests in the perpetuation of the regime and would make a safe ally. Leaders also try to create special relations with the higher ranks of the military, aiming at the satisfaction of their private interests, for example by looking the other way when it comes to corruption in armed forces. Beyond trying to establish privileged relations with both the civilians and the military, political leaders have, overtime, incremented specific sectors of internal security. First of all, the proliferation of internal security agencies and special units in the Arab states is a pretty common feature. Moreover, in some cases states have developed a fully-fledged dual military to potentially counter their regular armed forces.[2] Another means of political control is to maintain very large armies, because the presence of competitive subunits would serve as a material obstacle to the creation of anti-regimes coalitions. To conclude, leaders also try to guarantee sensitive positions within the military establishment to individuals whose loyalty to the regime is fairly secured. However, all of these measures come at a cost in terms of military effectiveness. The tactics and strategies developed to maintain civilian control over the military interfere with the actual capability of the armed forces to operate successfully, contradicting the efficiency and professionalism of military corps (Brooks 2004, 141).

*PART 2*

Building the primacy of the Turkish military

Zeki Sarigil divides the civil-military relations of the Turkish Republican history in two main periods: from the establishment of the Republic in 1923 up to the first 1960 coup, a first phase identified as “civilocracy” saw the military surely credited as a crucial institution, but still operating under civil governments. The first coup, triggered by the opening toward political pluralism in 1954, launched the “militocracy” era, that has been determined by a more independent stance of the military, now openly interfering with civilian power (Sarigil 2014, 172). From here, a further step can be recognized. The privileged role of the armed forces persisted untouched until the new millennium, when the combination of both external and internal elements caused a change in the pattern. The understanding of such reshaping helps shedding light on the failure of the last military coup, attempted in 2016 against Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s presidency.

The prominent role of the military in Turkey has first of all historical explanations, related both to the state building process of the state, as well as to its cultural characteristics. The army has in fact been the only institution to survive the end of the Ottoman Empire, and a primary actor in the process of foundation of the Republic. Turkey managed the transition from the Ottoman Empire to the new Republic under the lead of Mustafa Kemal (known as Ataturk, i.e. “the father of the Turks”). Coming from the military, Ataturk developed its modernization project under the principles of nationalism and secularism. He created a centralized bureaucracy, moving the capital to Ankara, while politically establishing a monopartite system guided by his Republican party. A high cultural modernization was then matched with scarce political pluralism and democratizing reforms. On the other hand, Ataturk elevated the army, bringing it beyond the mere military force and making it instead an institutional building. Over time, the army has taken upon both the role of founder and guardian of the new regime, as well as the one of protector of the Kemalist principles, i.e. secularism, cultural modernization and nationalism. Taking the cue from here, in the subsequent decades the army’s involvement in politics has been justified by this responsibility to protect the state from both domestic and foreign threats: as for the former, the main foes to the integrity of Kemalist principles and of modern Turkey have been identified with the potential Islamic reactionism and with the presence of Kurdish separatism.

The first Republican leaders succeeded to Ataturk saw the army as one of the main pillars of the regime, but they also understood how a potential involvement of the military in partisan politics could have been of detriment to both unity and discipline of the military itself (Narli 2000, 112). Despite this estrangement, the relevance of the army still echoed in the political life for different reasons: first, especially during the 1930s, the economic development plans were often determined taking into account military considerations; secondly, the military would remain a landmark in situations of emergencies, taking over civil administrative duties since it possessed the appropriate capabilities and facilities; third, the army was eventually part of the one-party design, instrumentalized by the Republican People’s Party for combating the internal reactionary forces. Hence, during the one-party rule of Republican history, the role of the army was central and its stance aligned with the principles animating the Kemalist political leaders. Thus, the interference with the political life of the country was not so openly visible.

Under these lenses, the 1950s represented a turning point for the civil-military relation in Turkey, as the country experienced a first opening toward political pluralism with the electoral successes of the Islamic-oriented Democratic Party – DP. The transition to a multi-party structure reinforced the guardianship role, leading to an active involvement of military forces through the practice of the coups d’état. Exactly since the 1950s, Turkey has been listed among hybrid regimes governed by tutelary democracy. A military tutelary regime is a political system providing on-duty and retired officers with rights and devices to deploy a certain degree of political power whenever they deem necessary (Caliskan 2017, 97). As mentioned before, according to Cook Turkey was in fact under the “tutelage” of a military that enjoyed broad autonomy within the political realm (Cook 2007). On the other hand, Turkey remained a democracy, since after every coup the army has retracted to the barracks in order to allow for elections. However, each intervention also widened the military’s prerogatives, increasing their power time after time (Gürsoy 2012, 741).

Since the Fifties, the military has directly intervened in Turkish politics three times (in 1960, 1971 and 1980), to which must be added the 1997 “postmodern” coup, and the 2016 failed one. The first coup d’état was carried out following increasing tensions between the Democratic Party-led government and the opposition forces, which resulted in large-scale students’ protests that ended with a bloody confrontation with the police forces, and eventually in the imposition of martial law in early 1960. To avoid the concrete risk of a civil war, the army stepped in on May 27 removing the government, dissolving the parliament and the Democratic Party itself. Moreover, Prime Minister Adnan Menderes was executed along with the Foreign Minister and the Minister of Finance. The military took command and instituted the National Security Council (Milli Güvenlik Kurulu – MGK): composed by the President, the Prime Minister, several other ministers, the Chief of General Staff and military force commanders, the MGK was entitled to provide recommendations to the government with regard to formulation and implementation of the state’s national security policy (Bilgiç 2009, 804). The armed forces dominated the political scene until 1965, when free elections were permitted again.

The 1965 round-voting resulted in the victory of the Justice Party[3] led by Süleyman Demirel. The critical economic situation of those years generated widespread instability and social unrest, followed by violent manifestation, planned leftists’ insurrections and trade unions’ opposition to the government economic programme. In March 1971, the military delivered an ultimatum to the President requiring the formation of a new government. Demirel resigned shortly after. In this case, the military didn’t impose a direct rule, but tried to guide the country’s democratic process, supporting the creation of a new governmental coalition.

The decade saw different coalitions trying impotently to deal with furtherly exacerbated civil polarization, while the violence and conflicts between left-wing and right-wing political organizations were leading the country on the verge of a civil war. Once again, in September 1980 the newly elected government led by Demirel was overthrown at the hand of the military in response to the domestic political anarchy. With the 1980 coup, the state apparatus became more militarized, universities were put under centralized control, and the 1982 Constitution limited the basic rights and liberties while strengthening the political autonomy of the military.

The 1997 indirect military intervention followed instead the 1995 general elections, where Necmettin Erbakan’s Welfare Party (Refah Partisi) obtained the majority. As observed by Caliskan with the rise of Erbakan’s Islamist party the labile balance between military and civilian rule that had been established in the previous decades was eventually destabilized (Caliskan 2017, 98). Erbakan in fact took aim at both military tutelage as well as at the western-secular connotation of Turkey. According to many civilians and military segments, the Kemalist principles of secularism were under threat because of the supposed anti-secular and anti-democratic stance of the Welfare Party. Consequently, the Turkish military issued a memorandum out of the 28 February 1997 meeting of the National Security Council, stating the generals’ wishes to the government and eventually forcing Erbakan out of power. Labelled as a “post-modern coup”, this operation enjoyed a wide support of the civil public especially because of the crucial role that mainstream media played in describing the Islamic identities of religious people as a source of internal security issues.

This civilian acquiescence with military interventions is indeed a recurrent feature of each coup. As underlined by Demirel, the Turkish military enjoyed its privileged place in the political realm also because it managed to achieve citizens’ consent to such a posture. This acceptance wasn’t attained only under the threat of arms, but also because the armed forces for decades had created the belief that they were an imperative condition for the survival of the country (Demirel 2004, 138). Additionally, the inability of civilian governments to guarantee economic and political stability strengthened this perception, providing the populations with a benchmark against which the military resulted as a safer choice.

These coups clearly display a military tradition that is attributing decisional power to the army, ready to intervene when the Kemalist principles and the safeguard of the country are being questioned. In allowing this constant presence of the military in both civil society and politics, the rules of the political game were changed, switching the role of elected governments from decision-makers actors to merely decision-practitioners. On the other hand, the role of the military steadily remained as a behind-the-curtain actor, able to influence both internal and foreign politics.

A New Perception of the Military

After nearly forty years of successful military interferences, the complete failure of the 2016 coup against Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s government comes thus as a novelty. The explanation of such outcome encompasses the analysis of external and internal elements that have helped reshape both the public understanding of the military and the military’s self-perception within the political realm.

A first crucial external factor is the prospect of EU membership between 1999 and 2006. The recognition of Turkey as a potential candidate in the 1999 Helsinki Summit triggered a series of reforms in the country, carried out especially under the Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi – AKP) government. The aim was to match the criteria required by European standards in terms of human rights protection, respect of the rule of law, presence of democratic institutions, and, most importantly, attainment of civilian control over the military. As for the latter, the reforms put in place regarded the civilian oversight of the defence expenditure, the role of the military in the judiciary, and several amendments to the MGK, meant in particular to narrow its powers and bringing its position back to the one envisioned in the 1960 Constitution (Gürsoy 2012, 743).

Secondly, the very same EU candidacy led the AKP government to take a different stance on the Cyprus situation. The division on the island risked becoming a serious obstacle for Turkish membership, since Cyprus was set to join the Union in 2004. Thus, the AKP government decided to support Kofi Annan’s plan to unify the Greek and Turkish communities on the island under a federal state. Eventually the project failed because of the rejection of the Greek Cypriots, but the Turkish civil government openly challenged the military that rooted instead for the continuation of the status quo based on the two separate and sovereign states (Özcan 2010, 12).

Third, the US invasion of Iraq helped shape a new approach in foreign policy with neighbours, as well as towards the Kurdish issue. As reported by Larrabee, Turkish public opinion was overwhelmingly opposed to the invasion (Larrabee 2010, 11-12). This widespread sentiment determined the Parliamentary vote of March 1, 2003, with which the Turkish Grand National Assembly would refuse to allow the US to use Turkish territory to open a second front against Iraq. As a consequence, the US withdrew the privileged position granted since 1991 to the Turkish military, that, as a partner of the Pentagon in the war, had access to the region. For the TAF it meant the loss of a strategic foothold, used to retaliate against the separatist activities carried out by the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) from its northern Iraq base. Consequently, the TAF found themselves without the support of the US ally nor influence in North Iraq in their activities against Kurdish separatism. The failure of the military brought the AKP to adopt a new approach with the neighbours, emphasising the use of soft power, of dialogue and economic cooperation. More in detail, the AKP government opened dialogue with the Kurdish regional government in northern Iraq, and domestically emphasized the individual rights and freedoms to minorities (Gürsoy 2012, 743).

At the internal level, the political and economic stability guaranteed by the AKP government led to a great public’s change in attitude toward the military. The 2002 elections conferred upon the AKP the mandate to form a new government, supported by the largest amount of votes any party had ever obtained in general elections since 1987.[4] The consequent political stability came as a coveted outcome after decades of unstable coalition ruling and great polarization among the population. Moreover, the popularity of the AKP was increased by a renewed economic stability, that resulted from measures undertaken by previous governments but of which the AKP government had the fortune of reaping the benefits during its term. Following the positive path, the government then developed a stabilization programme that succeeded in decreasing the inflation rate and expanding exports. In a country menaced by political instability and economic crises for over a decade, the soothing climate brought by the civil government came as a sigh of relief. Confident in the government’s capacities and relying on the political and economic stability, the majority of the population started reassessing the military’s involvement in the political realm.

How were these changes received by the armed forces? On the one hand, a section of hard-line military officers was concerned on several fronts (Gürsoy 2012, 747). Externally, they feared EU membership would have triggered Kurdish separatism and concessions on the Cyprus issue, eventually sparking a break-up of the Republic (Cizre and Walker 2010, 94). At the domestic level, some officers perceived the wave of reforms promoted by the AKP government as guided by an anti-secular Party with Islamic tendencies. On the other, these events were instead accepted by “moderate” officers. Their position can be summed up by the Chief of the General Staff Hilmi Özkök, who in early 2000 didn’t resist the potential EU membership and the reforms it meant. The accession to the EU surely included a downsizing of military power and privileges, but could have also served as a bulwark against Islamic radicalization and Kurdish separatism. As Bilgiç argues, the Europeanization reforms have not happened in spite of the military. On the contrary, the TAF have been involved in the process, influencing governmental decisions to an extent (Bilgiç 2009, 803).

In light of this analysis, the failure of the 2016 coup attempt seems more comprehensible. On July 15, a faction under the TAF – called Council for Peace at Home, Yurtta Sulh Konseyi – launched a coordinated attack to overthrow President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Later, the Turkish government blamed the coup on Hizmet[5], a movement headed by Fetullah Gülen who has lived in exile in the US since 1999. During the coup, Ankara and Istanbul were the scene of a series of explosions, while the tanks took the city streets. In order to succeed, the plotters should have had the population support and the military complete backup, but this time neither of those happened. First of all, many people took to the streets to resist the coup attempt, mobilized by social media. Additionally, the putschists were constituted by only a small group of Turkish troops and by civilian forces linked to FETÖ. They were thus acting outside the chain of command, while at the higher level the army leaders resisted the coup and remained loyal to the President.

The dynamics under which this last coup took place have therefore internalized the changes in both the military corps, that didn’t stand behind the coup but were instead divided in smaller factions, and in the population, that, satisfied with the current economic and political situation, resisted the plotters.

CONCLUSIONS

Traditional explanations approach the problem of MENA countries’ resistance to democratization trying to identify the prerequisites that the Middle East seems to lack. The geographical position, the weakness of civil societies, the state-controlled economy, the social condition of the population or the religious dimension cannot however be considered fully satisfying explanations, as other countries with the very same characteristics have managed transitioning toward democracy. As Eva Bellin has stated, the answer resides instead in the exceptionalism of the region, meaning in the peculiar conditions that enable the existence of a robust authoritarian apparatus. However, the circumstances that could determine a loosening of this coercive capacity, thus potentially enabling society to experiment with democratization, seem to not be reflected in current ME societies. Therefore, the analysis of the interrelations between military and civil forces became fundamental. From the point of view of civilian power, the main difficulty lies in ensuring civilian control over the military while still maintaining a strong army. The structural outputs of this encounter are several: the reflection of Steven Cook helps anticipate the Turkish framework, characterized by an indirect military rule: the military has in fact established shell pseudo-democratic institutions, handed to civilian allies. This institutional façade allows military officers to remain in control of the political developments through informal ties and control mechanisms, while letting other civilian actors to bear the burden of governing and of public discontent. Kamrava expands on this point, underlying that also more severe degrees of military influence in civilian affairs are possible, such as the cases of Egypt, Iraq or Algeria or of the monarchies. Authoritarian rulers have thus developed ad hoc strategies to bring the military back under civilian control. The “coup-proofing” tactics are in fact a common feature of ME political architecture, but they often are to the detriment of the army’s effectiveness, thus failing to reach the desired balance between a strong but controlled army.

Turkey is an interesting laboratory for the interplay of these dynamics. Almost every democratically elected leader had to face a certain degree of military intrusion in political affairs. Menderes was executed after the 1960 coup, Demirel was forced to resign twice following the 1971 and 1980 coups, while Erbakan had to do the same after the 1997 “soft-coup”. Erdoğan has been challenged more than once, while the most glaring attack had resulted in the failure of the 2016 coup.

The understanding of the role of the military in Turkish politics starts from its relevance in the Ottoman Empire and consolidates in the subsequent modern state-building process. Since the Ataturk rule, the TAF have projected themselves in the role of guardians of the Republic and of protectors of its Kemalist principles. This perception was shared by the public as well, that in front of the unsuccessful administration of many civilian governments accepted the guidance of the military. Under this civilian acquiescence, the TAF have directed national politics through four successful coups d’etat (in 1960, 1971, 1980 and 1997), dooming the role of elected governments from decision-makers to merely decision-practitioners. However, the 2016 failed coup reveals a different narrative. First, the prospect of EU membership gave the AKP government the chance to reform and downsize the influence of the military in politics, especially touching upon reforms to the MGK. Secondly, the Iraq War and the situation in Cyprus evidently displayed a loss of influence of the armed forces in foreign politics. At the internal level, the political and economic stability guaranteed by the AKP government resulted in the change of the public’s attitude toward the military. In front of these adjustments, a section of hard-line military officers was heavily concerned. On the other hand, the stance of the majority of the military, summarized by the Chief of the General Staff Hilmi Özkök’s opinion, didn’t resist the Europeanization period. Balancing the trade-off between the advancement it would have meant internally and the military downsizing it implicated, the “moderate” officers acknowledged the advantages the national state could have gained from the process.

These new dynamics, leading to reshaping both the public understanding of the military and the military’s self-perception within the political realm, have contributed to the failure of the 2016 coup. On the one hand the population, satisfied with the current economic and political situation, resisted the putschists. On the other, the military corps didn’t stand solidly behind the coup: they were instead divided in smaller factions, and the few troops participating in the attempt were assisted by civilians linked to FETÖ.

REFERENCES

Bellin, Eva. 2004. “The Robustness of Authoritarianism in the Middle East: Exceptionalism in Comparative Perspective”. Comparative Politics 36, no. 2: 139–57. https://doi.org/10.2307/4150140.

Bilgiç, Tuba Ünlü. 2009. “The Military and Europeanization Reforms in Turkey.” Middle Eastern Studies 45, no. 5: 803–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/00263200903135588.

Brooks, Risa. 2004. “Civil-Military Relations In The Middle East.” In The Future Security Environment in the Middle East: Conflict, Stability, and Political Change, edited by Nora Bensahel and Daniel L. Byman, 1st ed., 129–62. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7249/mr1640af.10.

Caliskan, Koray. 2017. “Explaining the end of military tutelary regime and the July 15 coup attempt in Turkey”, Journal of Cultural Economy, 10:1, 97-111. https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350.2016.1260628.

Cizre, Ümit and Joshua Walker. 2010. “Conceiving the New Turkey after Ergenekon”. The International Spectator 45, no. 1: 89 –98. https://doi.org/10.1080/03932721003661640.

Cook, Steven A. 2007. Ruling but not Governing: The Military and Political Development in Egypt, Algeria, and Turkey. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

Demirel, Tanel. 2004. “Soldiers and Civilians: The Dilemma of Turkish Democracy.” Middle Eastern Studies 40, no. 1: 127–50. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4289890.

Feaver, Peter D. 1996. “The Civil-Military Problematique: Huntington, Janowitz, and the Question of Civilian Control”, Armed Forces & Society, vol. 23 no. 2: 149-178. https://www.jstor.org/stable/45347059.

Gürsoy, Yaprak. 2012. “The changing role of the military in Turkish politics: democratization through coup plots?”, Democratization, 19:4, 735-760, https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2011.623352.

Juvenal. II century. “Satire VI”.

Kamrava, Mehran. 2000. “Military Professionalization and Civil-Military Relations in the Middle East.” Political Science Quarterly 115, no. 1: 67–92. https://doi.org/10.2307/2658034.

Kedourie, Ellie. 1994. Democracy and Arab Political Culture. London: Frank Cass.

Larrabee, F. Stephen. 2010. “Iraq and the Kurdish Challenge.” In Troubled Partnership: U.S.-Turkish Relations in an Era of Global Geopolitical Change, 11–32. RAND Corporation. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7249/mg899af.10.

Narli, Nilüfer. 2000. “Civil‐military relations in Turkey”. Turkish Studies, 1:1, 107-127. https://doi.org/10.1080/14683840008721223.

Norton, Augustus Richard. 1995-1996. Civil Society in the Middle East, vol. 1-2. Leiden: E.J. Brill.

Özcan, Gencer. 2010. “The Changing Role Of Turkey’s Military In Foreign Policy Making.” Revista UNISCI , no. 23: 23-45. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=76715004003.

Quinlivan, James T. 1999. “Coup-Proofing: Its Practice and Consequences in the Middle East.” International Security 24, no. 2: 131–65. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2539255.

Sarigil, Zeki. 2014. “The Turkish Military: Principal or Agent?” Armed Forces & Society 40, no. 1: 168–90. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48608989.

SIPRI. 2021. “Data for all countries from 1988–2020 as a share of GDP”. https://sipri.org/sites/default/files/Data%20for%20all%20countries%20from%201988%E2%80%932020%20as%20a%20share%20of%20GDP%20%28pdf%29.pdf.

Skocpol, Theda. 1979. States and Social Revolutions. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Wiktorowicz, Quintan. 2000. “Civil Society as Social Control: State Power in Jordan”. Comparative Politics 33, no. 1: 43–61. https://doi.org/10.2307/422423.

[1] Cook (2007, 139) brings the example of Sadat’s succession in Egypt: the 1971 Egyptian Constitution clearly states that, in case of a president’s incumbent retirement, resignation, incapacity or death, the speaker of the People’s Assembly should be next in line for presidency. Nevertheless, after Sadat’s death in 1981 he was succeeded by Hosni Mubarak, his vice-president and former Air Force General, who benefitted of the support of the officer corps.

[2] See as an example the Iraqi Republican Guard established during the 1980s and 1990s.

[3] The Justice Party (Adalet Partisi-AP) was founded in 1961 following the dissolution of the Democratic Party.

[4] In the 2002 general elections, the AKP won 34% of the votes, obtaining 66% of all seats.

[5] Referred to by the Government of Turkey as FETÖ – Fethullahist Terrorist Organisation, since 2016