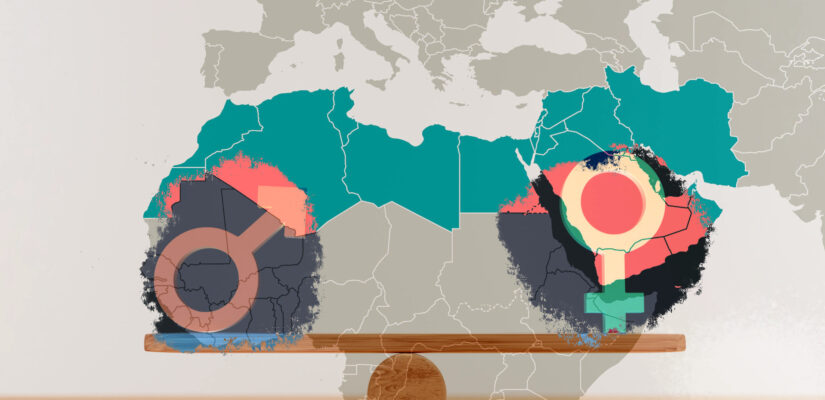

The Bumpy Road to Gender Equality in the MENA. Some Data-based Reflections

LORENA STELLA MARTINI

COMMENTARY #39 • MAY 2023

Gender equality has several, almost countless facets that could be analysed in a given context. For this reason, wondering whether gender equality is being achieved in a region as wide as the MENA certainly is a tricky as well as an extremely complex question to answer. What we can evaluate, however, is whether steps forward are being taken in some specific domains which are strongly relevant to this process. To do so, it is important not only to evaluate progress from the legislative or the quantitative point of view, but also to delve into women and men’s vision and perceptions of the issue at stake. Indeed, as we will soon see, developments which can be concretely measured – such as the number of women enrolled in universities, or the number of women in the workforce – can be easily questioned by a lack of change in societal mindset and norms, which remains key to reach gender equality effectively. On the other hand, however, structural barriers or political decisions limiting women’s empowerment also hamper processes of social change.

To make some open reflections on this issue with specific reference to the MENA region, we will stem from the data provided by the seventh wave of the Arab Barometer (October 2021-July 2022), related to surveys carried out in twelve countries of the enlarged MENA (Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Morocco, Mauritania, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, Iraq, Egypt, Sudan, and Kuwait) about women’s political leadership and representation, university education and access to the job market. The analysis of the results of this survey, together with data drawn from other sources, will give us the chance to raise some points and questions on gender inequality in the MENA region.

Political participation and leadership

In 9 out of 12 countries surveyed by the Arab Barometer, most interviewees (both male and female) agreed that “men are better at political leadership than women”. This view is mainly supported in Algeria (76% of the respondents) and Sudan (71%) while in Tunisia and Lebanon only a minority of respondents – but still up to 40% and 36% – did agree with it. The situation slightly improves if we only consider the answers given by women. Yet, only in four countries – Lebanon, Tunisia, Morocco, and Mauritania – do 50% or more of the women disagree with this statement. In this framework, it is telling to add that according to the Global Gender Gap Report 2022 of the World Economic Forum, the MENA region[1] is the third region in the world for gender imparity in the political field, ahead of East Asia and the Pacific and Central Asia only.

When considering women’s active participation in politics, Tunisia represents an interesting case: in 2010-2011, 72% of Tunisians surveyed by the Arab Barometer valued men’s political leadership more than women’s. More than ten years later, the percentage dropped to 40%, mirroring a path that Tunisia seemed to have embraced, even if not without difficulties, after the 2011 revolution, when female political representation started to grow, in line with new provisions to achieve gender equality included in the new constitutions and electoral law. For instance, in 2014, women held 32% of the seats in the Tunisian Parliamentary Assembly. Nevertheless, the current political situation in the country seems to have overturned this process: the new Parliament elected in 2023 counts on the lowest percentage of women’s seats since 2014 – and this, according to commentators, is mainly due to the electoral reform introduced by President Kais Saied ahead of the past elections, which eliminated previous gender parity provisions and made extremely difficult for women to meet new candidacy requirements.

Political evolutions concerning women’s political representation are also worth observing in Lebanon, the country in the Arab Barometer survey where the lowest percentage of citizens claimed that political leadership is mainly a men’s business. Again according to the Global Gender Gap Report 2022, the cabinet elected in 2020 made Lebanon the first country in the MENA region for number of women holding a ministerial position – one-third of government portfolios, a record for the country. The situation, however, dramatically changed in 2021, with the newly elected cabinet (currently holding power), which counts only one female minister, and in a non-top relevant domain (administrative development).

Nevertheless, the quantitative analysis of women’s representation in elective political institutions obviously is only one side of the coin. In Morocco, for example, the last elections held in September 2021 following a review of the legislative framework of the electoral process witnessed a very positive increase in women’s seats in the House of Representatives (from 20.5% to 24.3%), and a slight rise in the number of women’s seats in the House of Councillors (of less than 0.5%). The percentage of female ministers in the cabinet also rose from 16.7% to 28%, with 7 out of 25 ministries held by women, including in extremely relevant domains in absolute terms and for the country, such as Economy and Finance, Energy transition and Sustainable Development Tourism, Housing, Health and Social protection. At the same time, similar positive developments favoured by gender quota systems do generate questions about the real degree of empowerment and freedom given to women in the political field, given that the modality and extent of their political participation – in Morocco as elsewhere – mainly hinges upon rigid frameworks established from above.

University education & Access to work

Education is another key dossier to look at when assessing the status of gender equality. At a regional level, the picture is scarcely telling as it extensively varies on a country basis – namely if we consider that the MENA region is characterized by war-torn as well as by high-income countries, such as the Gulf ones. Anyhow, the regional average of girls enrolled in tertiary education according to the World Bank was 43% in 2020 – to provide benchmarks, the EU average was 84%, while Sub-Saharan Africa’s was 9%.

Assessing the number of girls enrolled in universities is certainly relevant – namely if we consider recent difficulties in accessing female education in countries such as Afghanistan, or recent episodes in Iran –, but it only depicts one part of the story. Indeed, it remains to be seen whether women’s increasing access to university education does lead to more opportunities in the job market, and whether changes in number are also supported by a real change of the patriarchal mindset well spread in the region when it comes to women reaching socio-economic independence.

Starting with the perception of women’s presence in universities across the region, according to the Arab Barometer only a minority of citizens in the twelve surveyed countries claimed that “university education is more important for men than for women”.

In particular, in Kuwait only 8% of the respondents values men’s university attendance more than women’s – a percentage that seems to be in line with the number of women enrolled in tertiary education in the Gulf country, which in 2020, according to the World Bank, reached 82%, rising from 28% in 2004 and 69% in 2014.

By comparing the results of the 2021-22 Arab Barometer survey with previous waves of this study asking similar questions, we observe that the trend of considering men worthier of university education than women has decreased across all countries in the last 15 to 10 years – except for Algeria. Indeed, the percentage of Algerians claiming a greater importance of men’s university education rose from 19% in 2006 (the year of the first Arab Barometer survey) to 30% in 2021-22. This is somehow curious if we consider that, according to the World Bank, the ratio of Algerian women enrolled in tertiary education is much higher than the men’s ratio (41% in 2021), and has increased from 24% in 2006 to 67% in 2021, while Algerian female academic staff has increased from 34% to 44%.

This fact hints at an important conclusion: although numbers might change towards more gender parity in key domains such as education or political participation, a change in the societal mindset is necessary in order to overcome gender-based bias, and actually reach gender equality.

Talking about women’s enrolment in universities is a prelude to dealing with their presence in the workforce. Here, the picture is sadly bleak: according to the World Bank, in 2021 only around 18% of women aged more than 15 participated in the labour force in the MENA region, as opposed to 70% of their male counterpart.

In this framework, it is interesting to understand what barriers women encounter to access the workforce and maintain their job in the MENA region. A majority, in the countries surveyed by the Arab Barometer thinks that the barriers women have to overcome are structural – such as lack of childcare and transportation, and low wages – rather than cultural. Nevertheless, cultural factors – such as the social unacceptability of women working, the lack of gender segregation at the workplace, and men being prioritized over women – are also taken into consideration by good percentages of the population in the surveyed countries, thus providing a multi-faceted picture of the challenges women have to deal with in the region to pursue a career.

Generally speaking, the lack of childcare was the more popular structural barrier mentioned by respondents to the Arab Barometer survey; against all expectations, in all countries less than 20% claimed that men are given priority over women in the job market. One of the reasons behind this result might be the lack of competition between men and women for the same work positions; indeed, the division of labour in the region is still highly gendered. Furthermore, women’s representation at senior management levels is still low, as well as in professional and technical jobs and entrepreneurship – even if with promising numbers in some domains, such as start-ups. Moreover, the number of female STEM graduates in the region has increased in the last few years; considering that graduates from such fields will be increasingly demanded in the future, there certainly is ground to improve female occupation – provided that the barriers mentioned above are addressed.

Zooming in on a country level, only in Libya were cultural barriers mentioned more often than structural ones when considering women’s access to the workforce; at the same time, Libya figures as the first country for number of respondents (24%) claiming that working is socially unacceptable for women. Since 2011 the country has been undergoing an extremely tense situation from the security point of view, one can’t help but wonder whether and how such conditions have influenced the perceptions of the Libyans – both men and women – in this domain.

[1] Sudan and Mauritania, which are included in the Arab Barometer’s survey, are not considered as part of the MENA region by the WEF Global Gender Gap Report.